Too Much of Nothing

What we learn from photographers' notion of 'negative space.'

One brief musing about storytelling per day (or, more likely, as frequently as I can muster).

Jan. 17, 2026

I’VE BEEN THINKING a lot about emptiness the past couple of weeks. Not in a personal emotional sense, but in a storytelling sense.

That’s because I’m in Beijing for a month, and my hotel room window looks out upon a neighborhood called Yong’anli that I used to wander around in. But since I was last here in 2017, a huge swath of it fell to what in urban China is known simply as 拆 — “demolish,” or “tear down.” It’s a pretty constant story of old Beijing crumbling as new Beijing, shinier and more income-producing, rises in its place.

Today, though, it stands as a fenced-in liminal space — a negative zone between yesterday’s life, which is gone, and tomorrow’s, which has yet to arrive.

We default to thinking of stories as things that happened, and most times they are. But sometimes, the best way to tell a story is to tell what didn’t happen — or what isn’t there, or how it feels to occupy what is called “negative space.”

Setting our minds to read this kind of landscape, either mentally or visually, is more challenging than it first seems. I think that’s for two reasons. Firstly, as I say, we are attuned to gravitate toward what has happened because it’s generally more straightforward and easier to corral. But that second reason is potent, too — the fact that thinking about what ISN’T there is a more abstract, and sometimes less visual, exercise that might not present itself as obviously and explicitly.

When you do start thinking about negative space, though, storytelling doors can open for you. So I want to take some glimpses at the notion today, and I invite anyone reading — visual storytellers in particular — to add to my admittedly meager knowledge of the topic.

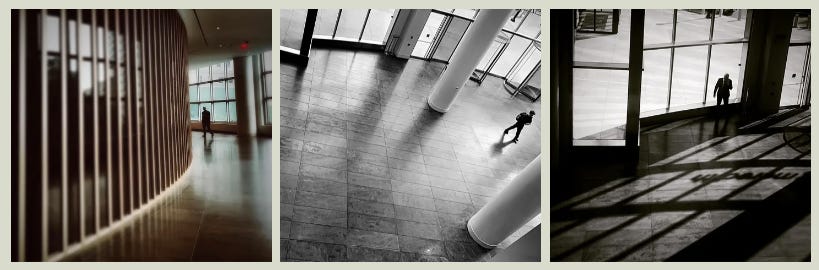

I’ve spent the past few years gathering what I perceive to be negative-space photos of the complex in New York City where I work. It has huge windows, curving hallways and vast lobbies that make me feel small, so when I see a lone figure walking or standing, it inspires me. The human figure itself isn’t the point of the image; its size is more of a “to-scale” indication of the environment around it. So in essence, these are photos of the place, not the person — but the person’s presence creates some tension and power in the storytelling. To me, they convey loneliness in the big city and something that is intended for humans but outscales them by a lot. Henri Cartier-Bresson was a master of this in his candid street photography images, which often used shadow and silhouette as tiny interruptions in larger landscapes of “negative space.”

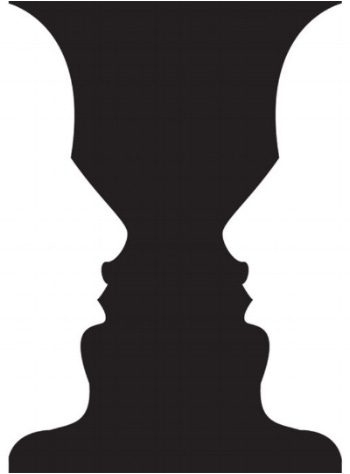

One of the first negative-space images I can remember was shown to me by my father after I saw something like it on the old Gen-X PBS show “The Electric Company.” It is a mind-teaser, essentially, a question: Is this a picture of a goblet or two people talking? Which part is the negative space? What does your brain tell you?

In storytelling, playing with negative space can do a number of things for you and your thinking.

It can show you what’s missing, which can be as strong a part of a story as what’s present — if you think about looking for it.

It can show you how small something is in its actual environment.

It can make a point about the space something takes up — and where it takes up that space.

It can catalogue things that haven’t been done, which is a way of showing something that has been done — and of making institutions and governments accountable.

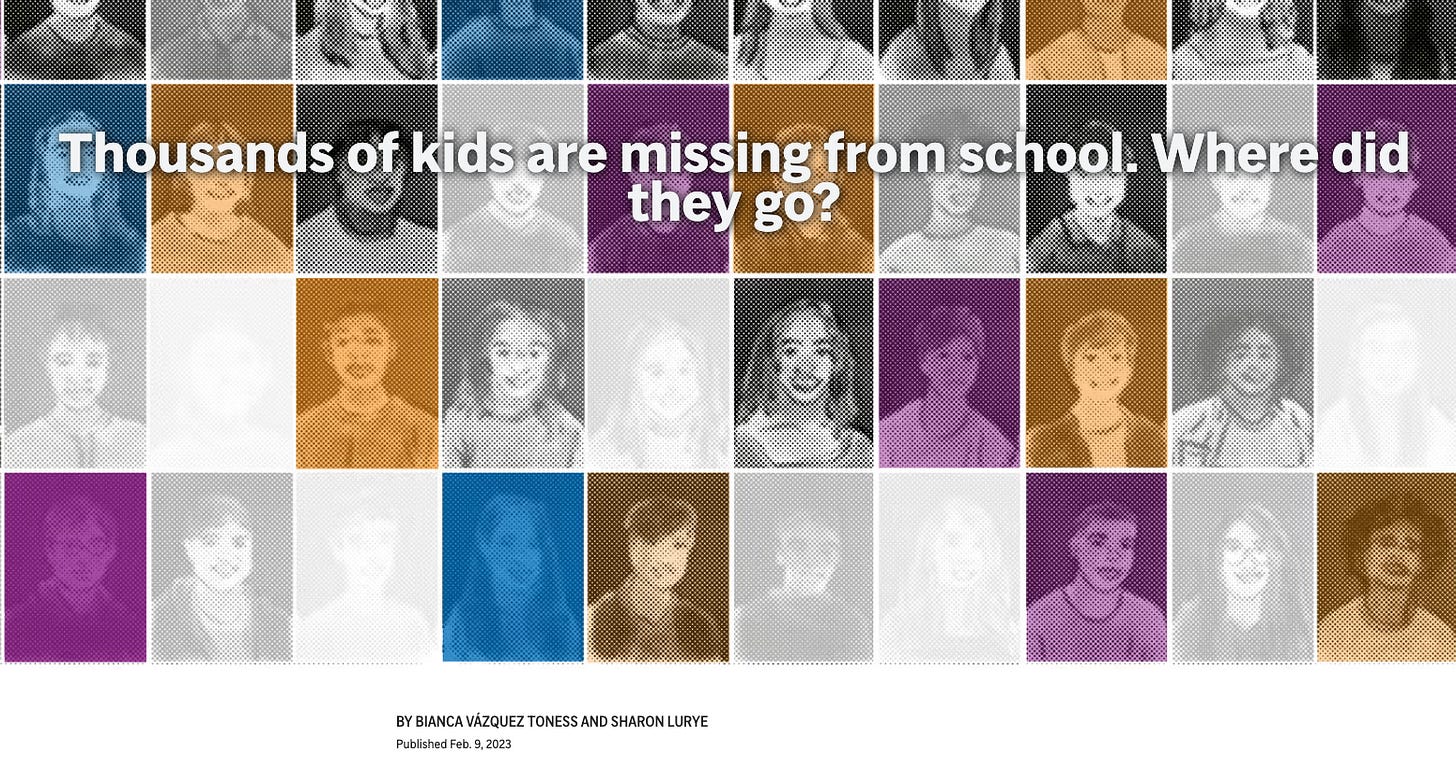

I don’t want to think about this only in a visual sense, though. “Negative space” is sometimes quite measurable. My incredible colleagues Bianca Vázquez Toness and Sharon Lurye wrote an unforgettable package a couple years ago about “missing kids” — those children who left school during the pandemic and never returned. The entire set of stories was a deeply reported and character-driven meditation on negative space — what wasn’t present and why.

Documenting absence is not an easy thing in storytelling. But when you do — whether it’s in a “What We Know” and “What We Don’t” format or a photograph that uses unused space to a powerful end — it can create memorable moments.

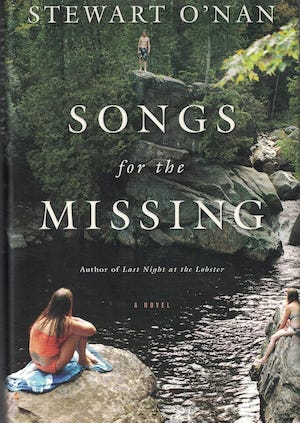

In fiction, the Pittsburgh author Stewart O’Nan offers an engaging example of this in his 2008 novel “Songs for the Missing,” a book-length examination of what a teenage girl’s disappearance does to her family. Slowly, meticulously, excruciatingly, he documents the days and weeks and months after Kim Larsen vanishes the summer before her freshman year of college — and the ways time passes in her family without her.

Let me leave you with one of the most powerful examples of negative space in recent American journalism. When reporter Evan Gershkovich of The Wall Street Journal was held in Russia for more than a year, his newspaper told the story of his absence by the absence of his story. Boldly, it left a huge chunk of prime real estate — its upper front page — absolutely blank, exploiting that negative space and the discomfort it conveys to the eye of a reader to drive home how unacceptable it saw Gershkovich’s imprisonment. The headline:

His story should be here

If you think that the absence of something can’t be powerful, just take one look at this — and think about how negative space might figure in your own storytelling.

And now, Peter, Paul and Mary.

To Ponder

What absences or missing things might you measure in your storytelling? How would you approach it?

In your “native format,” what are some techniques you might use to convey negative space — both small parts of a story and perhaps an entire story itself?

If you’re telling nonfiction stories, how might you research things that aren’t there? Are there techniques you might share?

Think about music you listen to. In a musical context, silence can be negative space. How is that used in music, and what does it accomplish?

Centralia, Pennsylvania, is a good example of negative space. The town, as I describe in my book, Fire Underground, was removed in the 1980s and 1990s as part of a government-ordered relocation to escape an underground fire in the labyrinth of abandoned coal mines beneath the town. When I go there today, I remember that some 400 or so homes, stores, schools and churches were once here where thickets of trees grow now. Only the cemeteries remain.

Great piece. If you don't know it, look up the story about why Dylan, who wrote the song, disliked the Peter, Paul and Mary cover. It makes another point about storytelling, which is the artist's attention to craft.